Lithium-ion Battery

A lithium-ion battery, also known as the Li-ion battery, is a type of secondary (rechargeable) battery composed of cells in which lithium ions move from the anode through an electrolyte to the cathode during discharge and back when charging.

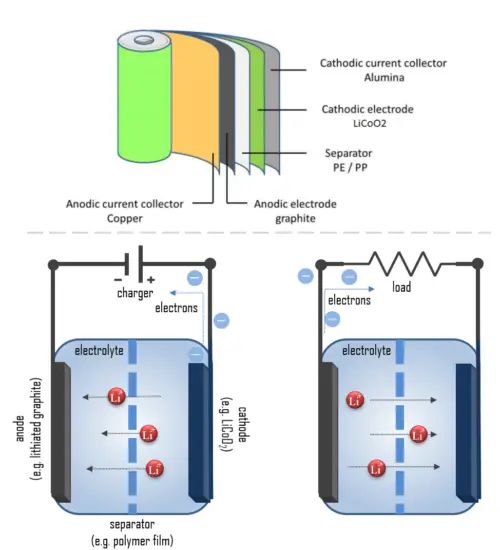

The cathode is made of a composite material (an intercalated lithium compound) and defines the name of the Li-ion battery cell. The anode is usually made out of porous lithiated graphite. The electrolyte can be liquid, polymer, or solid. The separator is porous to enable the transport of lithium ions and prevents the cell from short-circuiting and thermal runaway.

Chemistry, performance, cost, and safety characteristics vary across types of lithium-ion batteries. Handheld electronics mostly use lithium polymer batteries (with a polymer gel as electrolyte), a lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2) cathode material, and a graphite anode, which offer high energy density.

Li-ion batteries, in general, have a high energy density, no memory effect, and low self-discharge. One of the most common types of cells is 18650 battery, which is used in many laptop computer batteries, cordless power tools, certain electric cars, electric kick scooters, most e-bikes, portable power banks, and LED flashlights. The nominal voltage is 3.7 V.

Note that non-rechargeable primary lithium batteries (like lithium button cells CR2032 3V) must be distinguished from secondary lithium-ion or lithium-polymer, which are rechargeable batteries. Primary lithium batteries contain metallic lithium, which lithium-ion batteries do not.

Chemistry of Lithium-ion Battery – How it works

An electric battery is essentially a source of DC electrical energy. It converts stored chemical energy into electrical energy through an electrochemical process. This then provides a source of electromotive force to enable currents to flow in electric and electronic circuits. A typical battery consists of one or more voltaic cells.

The fundamental principle in an electrochemical cell is spontaneous redox reactions in two electrodes separated by an electrolyte, which is an ionic conductive and electrically insulated substance.

But how does such a battery work?

In simple terms, each battery is designed to keep the cathode and anode separated to prevent a reaction. The stored electrons will only flow when the circuit is closed. This happens when the battery is placed in a device and the device is turned on.

When the circuit is closed, the stronger attraction for the electrons by the cathode (e.g. LiCoO2 in lithium-ion batteries) will pull the electrons from the anode (e.g. lithium-graphite) through the wire in the circuit to the cathode electrode. This battery chemical reaction, this flow of electrons through the wire, is electricity.

If we go into detail, batteries convert chemical energy directly to electrical energy. Chemical energy can be stored, for example, in Zn or Li, which are high-energy metals because they are not stabilized by d-electron bonding, unlike transition metals. Lithium metal is the lightest metal and possesses a high specific capacity (3.86 Ah/g) and an extremely low electrode potential (−3.04 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode). Therefore lithium is an ideal anode material for high-voltage and high-energy batteries.

During discharge, lithium is oxidized from Li to Li+ (0 to +1 oxidation state) in the lithium-graphite anode through the following reaction:

C6Li → 6C(graphite) + Li+ + e–

These lithium ions migrate through the electrolyte medium to the cathode, where they are incorporated into lithium cobalt oxide through the following reaction, which reduces cobalt from a +4 to a +3 oxidation state:

CoO2 (s) + Li+ + e– → LiCoO2 (s)

Here is the full reaction (left to right = discharging, right to left = charging):

C6Li + CoO2 ⇄ C6 + LiCoO2

These reactions can be run in reverse to recharge the cell. In this case, the lithium ions leave the lithium cobalt oxide cathode and migrate back to the anode, where they are reduced back to neutral lithium and reincorporated into the graphite network.

Batteries convert chemical energy directly to electrical energy. Chemical energy can be stored, for example, in Zn or Li, which are high-energy metals because they are not stabilized by d-electron bonding, unlike transition metals.

Even though many types of batteries exist with different combinations of materials, all of them use the same principle of the oxidation-reduction reaction. In an electrochemical cell, spontaneous redox reactions take place in two electrodes separated by an electrolyte, which is an ionic conductive and electrically insulated substance. The redox reaction is a chemical reaction that produces a change in the oxidation states of the atoms involved. Electrons are transferred from one element to another. As a result, the donor element, which is the anode, is oxidized (loses electrons), and the receiver element, the cathode, is reduced (gains electrons).

For example, the lithium-ion cell consists of two electrodes of dissimilar materials. The cathode is made of composite material and defines the name of the Li-ion battery cell. Cathode materials are generally constructed from LiCoO2 or LiMn2O4. Anode materials are traditionally constructed from graphite and other carbon materials. Graphite is the dominant material because of its low voltage and excellent performance. The electrolyte can be liquid, polymer (with a polymer gel as electrolyte), or solid. The separator is porous to enable the transport of lithium ions and prevents the cell from short-circuiting and thermal runaway.

During the charging process, Li+ ions move from the Li-containing anode and pass through the electrolyte-soaked separator, finally intercalating to the anode host structure. As a result, the electrons pass through the external circuit in the opposite direction.

During discharge, electrons flow through the external circuit through the negative electrode (anode) towards the positive electrode (cathode). The reactions during discharge lower the chemical potential of the cell, so discharging transfers energy from the cell to wherever the electric current dissipates its energy, mostly in the external circuit. During charging, these reactions and transports go in the opposite direction.